Travel is often fun and relaxing – an escape from our everyday lives. But travel can also be an eye-opening experience – an opportunity to gain perspective and learn about the rest of the world. Sometimes the most meaningful travel experiences occur when you visit a place that teaches you something new and changes the way you look at the world around you.

During my thirteen months of travel, I visited several such places.

While in Vilnius, Lithuania, I heard of a unique excursion that I couldn’t pass up: a visit to a Soviet Bunker. This wasn’t so much a tour as it was a theatrical, interactive experience that at times felt very, very real. From the minute I arrived, it was like I was back in the year 1984, when Lithuania was part of the Soviet Union and when the Soviets maintained such bunkers in case of a nuclear war with the United States. Over three hours, I was berated in Russian, poked and prodded by a faux nurse, led up and down stairs and through dark hallways and forced to recite how great Lenin was. It truly opened my eyes to how life in the Soviet Union may have been. It made me appreciate the freedoms we have in the United States.

Just a week later, I was in Warsaw, a city that was almost wiped off the map by the Nazis in World War II. Reminders of the city’s tumultuous past surrounded me. Markers on the street showed where the walls of the Warsaw Ghetto once stood, imprisoning almost 400,000 Jews. Monuments honored those who fought against the Nazis. And the Warsaw Uprising Museum chronicled all of it, with photos and films and interviews with survivors. It was impossible to go a day without seeing something that brought a tear to my eye. Like other places I would visit on my trip, it made me appreciate how lucky we are that the United States has never fought a war on home soil in our lifetime.

That feeling was even stronger on a cloudy day in January, when I visited the Khatyn memorial, standing where the village of the same name once stood. Most people outside of Belarus have probably never heard of Khatyn. Most people probably don’t know that on March 22, 1943, German soldiers rounded up everyone in this small village, herded them into a barn and set the barn on fire. And then they encircled the barn, waiting with machine guns to shoot anyone who tried to escape the burning building. By the time the massacre ended, 149 people were killed, including 75 children.

And most people probably don’t know that this wasn’t an isolated incident. In addition to Khatyn, the Nazis burned down 185 villages in Belarus during World War II.

When I arrived at Khatyn, I heard bells chiming in thirty-second intervals. Those thirty seconds represented the rate at which Belarusians were killed during the war. In all, more than two million Belarusians died – one out of every four. That’s the equivalent of almost 33 million Americans dying in the war. Talk about perspective.

Not every place that made me stop and reflect involved war. I visited Chernobyl in the dead of winter, the ground covered with a couple feet of fresh snow. Touring the abandoned town of Pripyat felt like going back in time, but that wasn’t what moved me the most. Instead, I was struck by the narrative of the video we watched on the way there. Most of what I had heard about Chernobyl prior to visiting focused on the Soviet cover up of information and its failure to adequately address the ongoing consequences of Chernobyl.

But what stayed with me after my visit was how many people lost their lives trying to fight the fire in the nuclear power plant – and how close it came to being so much worse. In the days following the initial explosion, workers rushed to prevent a second explosion that had the potential to wipe out most of Europe. We can fault the Soviets for a lot of things related to Chernobyl, but we should also recognize the unprecedented situation they were dealing with and how hard they worked to prevent an even worse disaster.

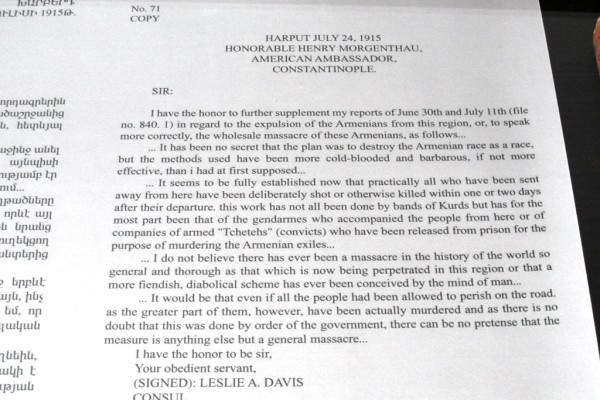

I knew almost nothing about Armenia before I arrived to spend five weeks there as a volunteer. I certainly didn’t know about the Armenian Genocide – when more than one million Armenians were killed by the Ottoman Turks between 1915 and 1923. Despite the existence of numerous eyewitness accounts and the fact that most historians classify the killings as genocide, the Turkish government refuses to acknowledge it and only twenty countries (not including the United States) have officially recognized the Armenian Genocide.

Walking through the Armenian Genocide Museum in Yerevan, I found it hard to believe that anyone could deny what happened. The proof was there in the letters from diplomats and aid workers who witnessed the atrocities, the photos that captured the dead and dying and the census records that revealed the extent the killing. It was heartbreaking.

What do all of these places have in common?

They all made me stop and think. They made me think about my life in the United States and how good we really have it. They made me think about how incredibly fortunate we are to have not fought a war on our soil in generations. Yes, we had the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon on September 11, 2001 that killed more than 3,000 people. But that seems like nothing compared to what happened in Armenia, Poland, Belarus and other countries during World Wars I and II.

They also made me think about how little we really learn about the rest of the world as we are growing up here. As I spoke with one woman in Belarus, she asked me this: “in the United States, who do you think won World War II?” I knew what she was getting at and I half-heartedly told her that we learned that the Allies won – the US, the Soviet Union, Britain, etc. But deep down, I knew I was lying – I suspect most kids today would simply say the US won. I am guessing most would be surprised to learn that the US and the Soviet Union were actually on the same side then.

It’s been nearly two decades since I was studying world history in high school and just slightly less time since I was majoring in Russian and East European Studies in college. I honestly don’t remember if I learned about 85% of Warsaw being destroyed or a quarter of the population of Belarus being killed. If I did, it certainly didn’t stay with me – likely because it was just words in a textbook and didn’t seem real.

Seeing these places, visiting the memorials and the museums, talking to people whose parents or grandparents experienced the events firsthand – those experiences made everything real. Over 13 months on the road, those were my most meaningful travel experiences.

They made me think, they changed my perspective and, most of all, they made me care.