I knew what I was getting into when I left. Just days before I got on the plan to Bamako, Mali, authorities ordered enhanced screening procedures for travelers returning from the West African nation due to a new outbreak of the Ebola virus. But I carefully read everything I could find on the CDC and other websites and was confident that, barring anything completely crazy happening, I would be considered extremely low risk, even no-risk, when I returned (for more on how it was to travel in Mali during the Ebola outbreak, check out my Mashable article).

So when I landed at Washington Dulles airport after 30 hours in transit, I thought I was prepared for what would happen.

One of the first off the flight from Addis Ababa, I approached the Global Entry kiosks, which were completely empty at 7:30 a.m. on a Sunday. After scanning my passport, a new question popped up: had I been to Guinea, Liberia, Sierra Leone or Mali in the last 21 days? My heart sank a little as I was kind of hoping Mali would not be included. It wasn’t included on the questionnaire required by Ethiopian health authorities and the country hadn’t had any new cases since before I arrived. Indeed, by the time I left Mali for Burkina Faso, there were no longer any active Ebola cases in the country.

I answered yes and immediately, rather than issuing me the normal Global Entry receipt that I would wave at officials on my way to baggage claim, I got a receipt with a large “X” across it, instructing me to report to Passport Control.

The officer on duty took a look and asked where I was coming from. As soon as I said Mali, he got on the phone to call someone to come get me. Within a minute or two, a Customs and Border Patrol officer was escorting me past baggage claim to an area beyond the notice of most passengers. He also asked me for my baggage claim stickers and told me he would have my bags brought to me. In my head, I was thinking that was completely unnecessary as I would probably be done with the enhanced screening before my bags even came off the conveyor belt.

Soon, I was sitting in a waiting area next to three gray cubicles. A thin man appeared from one of the cubes wearing goggles and a face mask and held up a thermometer near my forehead to take my temperature. Then he told me to wait until someone came to ask me the screening questions. Minutes later, two other men joined me – both African-American, I guessed father and son. They were from Texas and had been in Mali, visiting family in Bamako. The same man took their temperatures and instructed them to wait until someone showed up to screen them as well.

At this point, I could not help but wonder why on earth they didn’t have someone readily available to screen passengers arriving on a flight from Africa.

After forty minutes, I started to get annoyed and concerned that my enhanced screening may take longer than anticipated – all because they had no staff on duty to actually do the screening. I also realized that no one had brought me my bags yet and I began to worry whether or not I would be able to get them since I no longer had the baggage claim tags in my possession. I also began to wonder whether I would still have time to head into D.C. to pick up my winter coat from my friend Megan’s apartment before heading out to Reagan National for my Southwest flight to Chicago.

There was another guy hanging around who apparently worked there (although I never did figure out what his role was – he was just wearing jeans and a gray hoodie) so I started asking him questions, which turned into venting. He was sympathetic and set off to try to find my bags, but came back to tell me only that the claim tags had been given to the airline.

Finally, almost an hour after I first came back to the screening area, a CBP officer arrived and brought me back to another cubicle to sit down with him to go through the screening questions. As logged onto the computer, though, I could tell something was wrong.

Indeed, he soon confided in me that he had never done the screening before.

What?!? Again, with a flight from Africa landing, they had no one available who had experience screening for Ebola!? And why was a CBP officer screening me and not someone with medical training?

After consulting over the phone with someone named Vicky, the CBP officer figured out how to enter my information into the system and asked me a few simple questions – had I experienced any vomiting, diarrhea or fever? Had I been near anyone with those symptoms? Had I been in a hospital or lab with Ebola patients? Had I attended any funerals? Then, he just handed me a manila envelope that contained a thermometer and a variety of handouts about Ebola symptoms and contact information for health departments across the country and told me I was free to go. I had to remind him that I still needed my passport back and still needed to retrieve my bags.

It took talking to multiple CBP officers and multiple airline personnel, but I finally was able to retrieve my bags from outside baggage claim. But while I had my passport back, I did not have my Global Entry form, so they would not let me leave the airport yet. I had to return to the screening area and find the CBP officer who still had the form. By this time, he was interviewing the two African-American men who had arrived after me. I knew from talking with them that they certainly were at no greater risk than I was, but I couldn’t help but notice the officer was wearing a protective mask to meet with them while he had not worn anything as he talked to me. Hmmm.

I made it back to Chicago later that night without incident and mid-morning on Monday, I got a call from a doctor with the Chicago Department of Public Health. She could not have been nicer and assured me that she knew I was very, very low risk. At the same time, she revealed that my temperature at the airport had actually been 99.7 – not so far away from the 100.4 threshold for a fever! She explained that I would need to text a nurse my temperature each morning and night for the next 13 days (since I had already been out of Mali for eight days). I would also get one at-home visit a week during that period. After I explained to her more details from my trip, she reiterated that she really thought I was extremely low risk and that there would be no restrictions on my movement or interactions with people – as long as I didn’t develop any symptoms of Ebola.

She also pointed out something I had not considered: that it was the heart of cold and flu season and I would need to be careful to avoid people who may get me sick – because if I suddenly spiked a fever, they would have to initially treat it as if I may have Ebola, which would be a huge pain for everyone involved.

And then something else happened that I had not anticipated: I got uninvited to a party.

A few friends decided they didn’t feel comfortable being around me and any “weird African diseases” I may have been exposed to. I was shocked and saddened and disappointed. Sure, I had heard plenty of stories of others overreacting to Ebola (a teacher who had to take a three-week leave after attending a conference in Dallas and a child who wasn’t allowed back to school for three weeks after a visit to Nigeria even after the country was declared Ebola-free are just two examples). But I definitely didn’t expect friends who have known me for years to buy into the Ebola hysteria. No matter that Ebola isn’t spread through the air, that no one is known to have caught it at an airport or on an airplane and that even if I was exposed I wouldn’t be contagious unless I was showing symptoms (in which case I certainly wouldn’t go out in public).

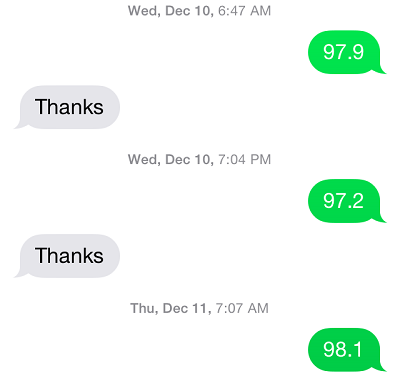

Once I got over my initial anger and disappointment, though, I saw it as a wake-up call. I realized that people very well could see me as a threat so I made the decision to lay low as much as possible. I skipped a couple other holiday parties my first week back (including one that I knew would include someone who had freaked out over the U.S. bringing Kent Brantly and Nancy Writebol back to the country for treatment). My second week back, I ventured out a few times but was careful not to talk about my trip with anyone I didn’t know well. In the meantime, I dutifully texted my temperature to my assigned nurse morning and night (which interestingly never topped 98.1) and did my best to avoid anyone who might give me the flu or a cold.

The two weeks passed quickly. As I write this, I am on the last day of my monitoring period. I’ll send one last text message to my nurse tonight and then will receive a certificate tomorrow indicating that I was monitored for Ebola and never got it. One last souvenir from my trip, I guess.